myoldmac.net

Secrets

of the Little Blue Box

A story so incredible it may

even make you feel sorry for the phone companys...

The Official Phreaker's Manual - by Ron

Rosenbaum

Printed in the October 1971 issue of Esquire

Magazine. If you happen to be in a library and

come across a collection of Esquire magazines,

the October 1971 issue is the first issue printed

in the smaller format. The story begins on page

116 with a picture of a blue box.

Note by the Webmaster: I

found this note about the following

Esquire article,

written by John

T Draper (AKA Captain Crunch)

Quote Captain Crunch: "After

the Esquire article came out, Steve

Wozniak read it and found

it fascinating, and really wanted

to build the blue box and play

with it himself. It didn't take

him long to realize that the tone

frequency combinations used in

the article were deliberately changed

to protect this fatal flaw in Ma

bell.

Woz contacted me somehow, through

KKUP radio, where another DJ from

KPFA knew me and mentioned to Woz

that he knew me. The KPFA DJ called

me up and told me to contact Woz.

At first, I didn't think it was safe

to discuss this with a stranger,

but I finally agreed to phone Woz.

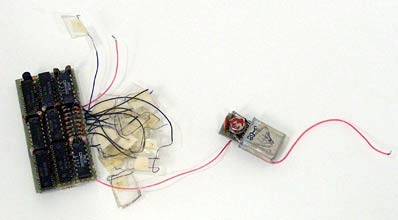

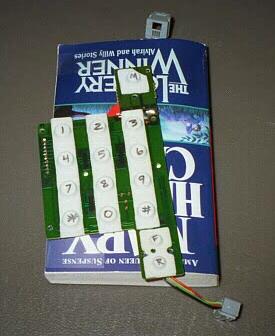

Blue Box - Manufacturer:

Stephen Wozniak - Date: c. 1972

Courtesy of Allen

Baum

I called him up, and he was really

excited that I actually would call

him, and talked me into driving to

Berkeley to visit him. I finally

locate the dorm where Woz, Steve

Jobs, and Bill Klaxton was waiting

for me. After the usual introductions,

it became obvious that Woz didn't

know how to use the blue box, and

I didn't want Woz to misuse it and

eventually get detected, so I took

time to explain the do's and don'ts

on using this amazing tone device.

Woz was relentless in his questions

and I was patient enough to tell

him how to make international calls,

so for fun we tried to call the Pope

in Rome. For those that don't know

the Woz, he just loves to play pranks

on everyone. Woz wanted to call the

Pope and make a "Confession".

By this time, I said to myself... "These

crazy college kids!" After Woz's

lesson, I eventually left, with a

stern warning to Woz not to make

and sell them, because this would

cause problems for all of us.

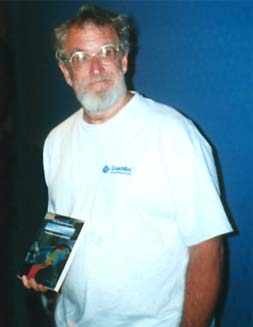

John Draper aka Captain Crunch and Oliver from myoldmac.net at

Computer Gaming Museum Berlin 2012

Woz got a little greedy and made

enough of them to sell for enough

money for school, and to fund his

computer project which eventually

became the Apple I. I repeatedly

contacted Woz to make sure he wasn't

misusing the box, and eventually

learned he was selling them for $150

a piece. In each one, he had an inscription "He

has the whole world in his hands",

and instructions for making international

calls.

One day, when Woz was driving from

his parents home in Sunnyvale to

UC Berkeley, his car broke down somewhere

near Fremont. So he thought he would

try and use his blue box to place

a call. Just then, a police car pulls

up and a policeman gets out and asks

Woz for his ID. As the cop was checking

things out, he noticed the box sitting

in the pay phone and asked "What's

that?". Woz said "It's

my Synthesizer for an electronic

project". The cop was pressing

the buttons, playing with it, then

handed it hack and said "A guy

named Moog beat you to it" and

left.

Woz sold the box to another acquaintance

who was totally uncool and eventually

brought me to the attention of Bell

Security by his constant bragging

about his ability to make free calls.

He was in a San Jose high school

and mentioned my name to his school's

Activities Director. Nothing came

of it, but I tried to distance myself

from him as much as possible.

Eventually, this kid got busted,

who had Woz's box. From that time

on, we all agreed to lay low and

not mess with anything for a while.

More and more of Woz's customers

got busted, mostly for leaving tell

tale evidence by making a large amount

of 800 number calls."

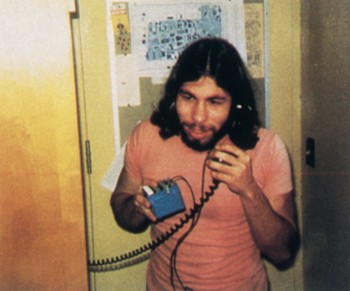

Steve WOZniak Phone

Phreakin´ |

This note about

t the Blue Box is directly written

by Steve Wozniak - source: www.woz.org

Q From e-mail:

How did you make the blue box?

Do you still own one? Also..

Do you have the apple I still

or any screen shots of it and

programs? If so send me some.

Thanks,Andy age:12

WOZ:

I read an article in Esquire Magazine.

It was about the October edition

in 1971. The article was entitled "Secrets

of the Blue Box--fiction" by

Ron Rosenblum. Halfway through

the article I had to call my best

friend, Steve Jobs, and read parts

of this long article to him. It

was about secret engineers that

had special equipment in vans that

could tap into phone cables and

redirect the phone networks of

the world. The article had blind

phone phreaks like Joe Engessia

Jr. of Nashville, and the hero

of them all, Captain Crunch. It

was a science fiction world but

was told in a very real way. Too

real a way. I stopped and told

Steve that it sounded real, not

like fiction. They gave too many

engineering details and talked

on too real a way to have been

made up. They even gave out some

of the frequencies that the blue

box used to take control of the

international phone network.

The next day was Sunday. Steve and

I drove to SLAC (Stanford Linear

Accelerator Center, the same place

the Homebrew Computer Club would

meet 4 years later) because they

always left a door or two unlocked

and nobody thought anything about

a couple of strangers reading books

and magazines in their technical

library. Finally we found a book

that had the exact same frequencies

that had been mentioned in the Esquire

article. Now we had the complete

list.

We went back to Steve's house and

built two, somewhat unstable, multivabrator

oscillators. We could see the instability

on a frequency counter, but we were

in a hurry. We would set one oscillator

to 700 Hz and the other to 900 Hz

(for a "1") and record

it on a tape recorder. Then we'd

adjust the oscillators and record

the next digit, and so on. But it

wasn't good enough to make a call

as in the article. So we tried one

oscillator at a time. It still wasn't

good enough. I was off to Berkeley

the next day so it would be some

weeks before I designed a digital

blue box that never missed a note.

The key to debugging it was a guy

in the dorm, Mike Joseph, that had

perfect pitch. If it didn't work,

he'd tell me what notes he heard.

If one of them was a C-sharp and

was supposed to be an A, I could

look up the C-sharp frequency and

find out where my frequency divider

was off, and replace a diode that

was bad. All my problems were diodes

that I bought at Radio Shack in a

bag where some might actually work.

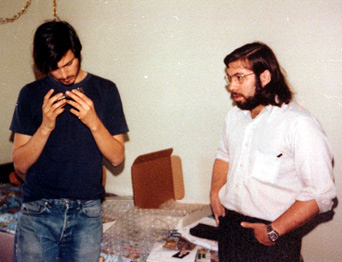

Steve Jobs and Steve

Wozniak in 1975 with a Blue Box -

found at woz.org

The key to the phone network then

was a high E note, two octaves above

the high E string on a guitar. It

was 2600 Hz. The Captain Crunch cerial

whistle could blow this note and

seize a phone line. The blue box

then took over with it's dual frequency

combinations known as 'multfrequency'

or MF, similar to touch tone frequencies

but not the same. Some phone systems

worked on SF, or Single Frequency.

The 2600 Hz Captain Crunch whistle

could make the entire call. One long

whistle to seize the line, a short

one for a "1", two short

ones for a "2", etc. The

blind phone phreak, Joe Engressia,

could dial an entire call just by

whistling it out of his own mouth!

If you want to test this principal,

play 2600 Hz into and long distance

call and you'll be disconnected.

We had fun doing that in the dorms.

But don't be stupid and try to make

a blue box today. It's much easier

to make or program, but you're nearly

guaranteed to get caught right away

in most places. I experimented with

it in 1972 but even then I paid for

my own calls. I only used the blue

box to see how many things I could

do.

I have Apple I's and original software

and things but they're in storage

and I don't have time to get them

out and get them working right now. |

The Official Phreaker's Manual

Printed in the October 1971

issue of Esquire Magazine.

The Blue Box Is Introduced:

Its Qualities Are Remarked

I am in the expensively furnished living room

of Al Gilbertson (His real name has been changed.),

the creator of the "blue box." Gilbertson

is holding one of his shiny black-and-silver "blue

boxes" comfortably in the palm of his hand,

pointing out the thirteen little red push buttons

sticking up from the console.

He is dancing his fingers over the buttons,

tapping out discordant beeping electronic jingles.

He is trying to explain to me how his little

blue box does nothing less than place the entire

telephone system of the world, satellites, cables

and all, at the service of the blue-box operator,

free of charge. "That's what it does. Essentially

it gives you the power of a super operator. You

seize a tandem with this top button," he

presses the top button with his index finger

and the blue box emits a high-pitched cheep, "and

like that" -- cheep goes the blue box again

-- "you control the phone company's long-distance

switching systems from your cute little Princes

phone or any old pay phone. And you've got anonymity.

The phone company knows where she is and what

she's doing. But with your beeper box, once you

hop onto a trunk, say from a Holiday Inn 800

(toll-free) number, they don't know where you

are, or where you're coming from, they don't

know how you slipped into their lines and popped

up in that 800 number. They don't even know anything

illegal is going on. And you can obscure your

origins through as many levels as you like. You

can call next door by way of White Plains, then

over to Liverpool by cable, and then back here

by satellite. You can call yourself from one

pay phone all the way around the world to a pay

phone next to you. And you get your dime back

too." "And they can't trace the calls?

They can't charge you?"

"Not if you do it the right way. But you'll

find that the free-call thing isn't really as

exciting at first as the feeling of power you

get from having one of these babies in your hand.

I've watched people when they first get hold

of one of these things and start using it, and

discover they can make connections, set up crisscross

and zigzag switching patterns back and forth

across the world. They hardly talk to the people

they finally reach. They say hello and start

thinking of what kind of call to make next. They

go a little crazy." He looks down at the

neat little package in his palm. His fingers

are still dancing, tapping out beeper patterns. "I

think it's something to do with how small my

models are. There are lots of blue boxes around,

but mine are the smallest and most sophisticated

electronically. I wish I could show you the prototype

we made for our big syndicate order." He

sighs. "We had this order for a thousand

beeper boxes from a syndicate front man in Las

Vegas. They use them to place bets coast to coast,

keep lines open for hours, all of which can get

expensive if you have to pay. The deal was a

thousand blue boxes for $300 apiece. Before then

we retailed them for $1500 apiece, but $300,000

in one lump was hard to turn down. We had a manufacturing

deal worked out in the Philippines.

Everything ready to go. Anyway, the model I

had ready for limited mass production was small

enough to fit inside a flip-top Marlboro box.

It had flush touch panels for a keyboard, rather

than these unsightly buttons, sticking out. Looked

just like a tiny portable radio. In fact, I had

designed it with a tiny transistor receiver to

get one AM channel, so in case the law became

suspicious the owner could switch on the radio

part, start snapping his fingers, and no one

could tell anything illegal was going on. I thought

of everything for this model -- I had it lined

with a band of thermite which could be ignited

by radio signal from a tiny button transmitter

on your belt, so it could be burned to ashes

instantly in case of a bust. It was beautiful.

A beautiful little machine. You should have seen

the faces on these syndicate guys when they came

back after trying it out. They'd hold it in their

palm like they never wanted to let it go, and

they'd say, 'I can't believe it. I can't believe

it.' You probably won't believe it until you

try it."

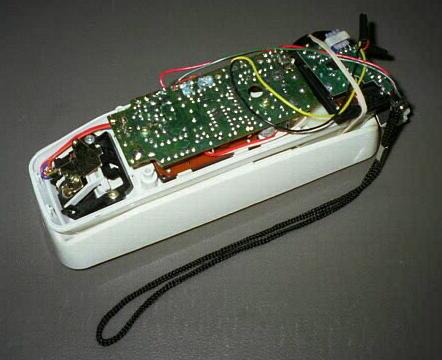

Blue

Box in Museum - Copyright RaD man.

Cropped by David Remahl 2004.

The blue box previously owned by Steve

Wozniak, on display at the Computer

History Museum

The Blue Box Is Tested: Certain Connections

Are Made

About eleven o'clock two nights later Fraser

Lucey has a blue box in the palm of his left

hand and a phone in the palm of his right. He

is standing inside a phone booth next to an isolated

shut-down motel off Highway 1. I am standing

outside the phone booth. Fraser likes to show

off his blue box for people. Until a few weeks

ago when Pacific Telephone made a few arrests

in his city, Fraser Lucey liked to bring his

blue box (This particular blue box, like most

blue boxes, is not blue. Blue boxes have come

to be called "blue boxes"

either because 1) The first blue box ever confiscated

by phone-company security men happened to be

blue, or 2) To distinguish them from "black

boxes."

Black boxes are devices, usually a resistor in

series, which, when attached to home phones,

allow all incoming calls to be made without charge

to one's caller.) to parties. It never failed:

a few cheeps from his device and Fraser became

the center of attention at the very hippest of

gatherings, playing phone tricks and doing request

numbers for hours. He began to take orders for

his manufacturer in Mexico. He became a dealer.

Fraser is cautious now about where he shows

off his blue box. But he never gets tired of

playing with it. "It's like the first time

every time," he tells me. Fraser puts a

dime in the slot. He listens for a tone and holds

the receiver up to my ear. I hear the tone. Fraser

begins describing, with a certain practiced air,

what he does while he does it. "I'm dialing

an 800 number now. Any 800 number will do. It's

toll free. Tonight I think I'll use the -----

(he names a well-know rent-a-car company) 800

number. Listen, It's ringing. Here, you hear

it? Now watch." He places the blue box over

the mouthpiece of the phone so that the one silver

and twelve black push buttons are facing up toward

me. He presses the silver button -- the one at

the top -- and I hear that high-pitched beep.

"That's 2600 cycles per second to be exact,"

says Lucey. "Now, quick. listen." He

shoves the earpiece at me. The ringing has vanished.

Wozniak's Blue Box - ca 1972

- Found at computerhistory.org

The line gives a slight hiccough, there is a

sharp buzz, and then nothing but soft white noise.

"We're home free now," Lucey tells

me, taking back the phone and applying the blue

box to its mouthpiece once again. "We're

up on a tandem, into a long-lines trunk. Once

you're up on a tandem, you can send yourself

anywhere you want to go." He decides to

check out London first. He chooses a certain

pay phone located in Waterloo Station. This particular

pay phone is popular with the phone-phreaks network

because there are usually people walking by at

all hours who will pick it up and talk for a

while. of the box. "That's Key Pulse. It

tells the tandem we're ready to give it instructions.

First I'll punch out KP 182 START, which will

slide us into the overseas sender in White Plains." I

hear a neat clunk-cheep. "I think we'll

head over to England by satellite. Cable is actually

faster and the connection is somewhat better,

but I like going by satellite. So I just punch

out KP Zero 44. The Zero is supposed to guarantee

a satellite connection and 44 is the country

code for England. Okay... we're there. In Liverpool

actually. Now all I have to do is punch out the

London area code which is 1, and dial up the

pay phone. Here, listen, I've got a ring now." I

hear the soft quick purr-purr of a London ring.

Then someone picks up the phone.

"Hello," says the London voice.

"Hello. Who's this?" Fraser asks.

"Hello. There's actually nobody here. I

just picked this up while I was passing by. This

is a public phone. There's no one here to answer

actually."

"Hello. Don't hang up. I'm calling from

the United States.",

"Oh. What is the purpose of the call? This

is a public phone you know."

"Oh. You know. To check out, uh, to find

out what's going on in London. How is it there?"

"Its five o'clock in the morning. It's raining

now."

"Oh. Who are you?"

The London passerby turns out to be an R.A.F.

enlistee on his way back to the base in Lincolnshire,

with a terrible hangover after a thirty-six-hour

pass.

He and Fraser talk about the rain. They agree

that it's nicer when it's not raining. They say

good-bye and Fraser hangs up. His dime returns

with a nice clink.

"Isn't that far out," he says grinning

at me. "London, like that." Fraser

squeezes the little blue box affectionately in

his palm.

"I told ya this thing is for real. Listen,

if you don't mind I'm gonna try this girl I know

in Paris. I usually give her a call around this

time. It freaks her out. This time I'll use the

------ (a different rent-a-car company) 800 number

and we'll go by overseas cable, 133; 33 is the

country code for France, the 1 sends you by cable.

Okay, here we go.... Oh damn. Busy. Who could

she be talking to at this time?"

A state police car cruises slowly by the motel.

The car does not stop, but Fraser gets nervous.

We hop back into his car and drive ten miles

in the opposite direction until we reach a Texaco

station locked up for the night. We pull up to

a phone booth by the tire pump. Fraser dashes

inside and tries the Paris number. It is busy

again.

"I don't understand who she could be talking

to. The circuits may be busy. It's too bad I

haven't learned how to tap into lines overseas

with this thing yet."

Fraser begins to phreak around, as the phone

phreaks say. He dials a leading nationwide charge

card's 800 number and punches out the tones that

bring him the time recording in Sydney, Australia.

He beeps up the weather recording in Rome, in

Italian of course. He calls a friend in Boston

and talks about a certain over-the-counter stock

they are into heavily. He finds the Paris number

busy again. He calls up "Dial a Disc"

in London, and we listen to Double Barrel by

David and Ansil Collins, the number-one hit of

the week in London. He calls up a dealer of another

sort and talks in code. He calls up Joe Engressia,

the original blind phone-phreak genius, and pays

his respects. There are other calls. Finally

Fraser gets through to his young lady in Paris.

They both agree the circuits must have been

busy, and criticize the Paris telephone system.

At two-thirty in the morning Fraser hangs up,

pockets his dime, and drives off, steering with

one hand, holding what he calls his "lovely

little blue box"

in the other.

John Draper is holding the book "Hackertales" (www.hackertales.de) which includes his life story, if you have wondered what he is holding. Photo courtessy of Evrim Sen.

John "Captain Crunch"

Draper

Formerly a Phone Phreak, John Draper once gained

fame (and prison sentences) from his skills in

manipulating the telephone system. His "handle"

came from the inclusion of a plastic whistle

in Captain Crunch cereal in the 1960's which

could, with proper manipulation, send out a control

tone that would affect telephone systems of the

time.

You Can Call Long Distance For Less Than You

Think

"You see, a few years ago the phone company

made one big mistake," Gilbertson explains

two days later in his apartment. "They were

careless enough to let some technical journal

publish the actual frequencies used to create

all their multi-frequency tones. Just a theoretical

article some Bell Telephone Laboratories engineer

was doing about switching theory, and he listed

the tones in passing. At ----- (a well-known

technical school) I had been fooling around with

phones for several years before I came across

a copy of the journal in the engineering library.

I ran back to the lab and it took maybe twelve

hours from the time I saw that article to put

together the first working blue box. It was bigger

and clumsier than this little baby, but it worked."

It's all there on public record in that technical

journal written mainly by Bell Lab people for

other telephone engineers. Or at least it was

public. "Just try and get a copy of that

issue at some engineering-school library now.

Bell has had them all red-tagged and withdrawn

from circulation," Gilbertson tells me.

"But it's too late. It's all public now.

And once they became public the technology needed

to create your own beeper device is within the

range of any twelve-year-old kid, any twelve-year-old

blind kid as a matter of fact. And he can do

it in less than the twelve hours it took us.

Blind kids do it all the time. They can't build

anything as precise and compact as my beeper

box, but theirs can do anything mine can do."

"How?"

"Okay. About twenty years ago A.T.&T.

made a multi-billion-dollar decision to operate

its entire long-distance switching system on

twelve electronically generated combinations

of twelve master tones. Those are the tones you

sometimes hear in the background after you've

dialed a long-distance number. They decided to

use some very simple tones -- the tone for each

number is just two fixed single-frequency tones

played simultaneously to create a certain beat

frequency. Like 1300 cycles per second and 900

cycles per second played together give you the

tone for digit 5. Now, what some of these phone

phreaks have done is get themselves access to

an electric organ. Any cheap family home-entertainment

organ. Since the frequencies are public knowledge

now -- one blind phone phreak has even had them

recorded in one of the talking books for the

blind -- they just have to find the musical notes

on the organ which correspond to the phone tones.

Then they tape them. For instance, to get Ma

Bell's tone for the number 1, you press down

organ keys FD5 and AD5 (900 and 700 cycles per

second) at the same time. To produce the tone

for 2 it's FD5 and CD6 (1100 and 700 c.p.s).

The phone phreaks circulate the whole list of

notes so there's no trial and error anymore."

He shows me a list of the rest of the phone

numbers and the two electric organ keys that

produce them.

"Actually, you have to record these notes

at 3 3/4 inches-per-second tape speed and double

it to 7 1/2 inches-per-second when you play them

back, to get the proper tones," he adds.

"So once you have all the tones recorded,

how do you plug them into the phone system?"

"Well, they take their organ and their

cassette recorder, and start banging out entire

phone numbers in tones on the organ, including

country codes, routing instructions, 'KP' and

'Start' tones. Or, if they don't have an organ,

someone in the phone-phreak network sends them

a cassette with all the tones recorded, with

a voice saying 'Number one,' then you have the

tone, 'Number two,' then the tone and so on.

So with two cassette recorders they can put together

a series of phone numbers by switching back and

forth from number to number. Any idiot in the

country with a cheap cassette recorder can make

all the free calls he wants."

"You mean you just hold the cassette recorder

up the mouthpiece and switch in a series of beeps

you've recorded? The phone thinks that anything

that makes these tones must be its own equipment?"

"Right. As long as you get the frequency

within thirty cycles per second of the phone

company's tones, the phone equipment thinks it

hears its own voice talking to it. The original

granddaddy phone phreak was this blind kid with

perfect pitch, Joe Engressia, who used to whistle

into the phone. An operator could tell the difference

between his whistle and the phone company's electronic

tone generator, but the phone company's switching

circuit can't tell them apart. The bigger the

phone company gets and the further away from

human operators it gets, the more vulnerable

it becomes to all sorts of phone phreaking."

A Guide for the Perplexed

"But wait a minute," I stop Gilbertson.

"If everything you do sounds like phone-company

equipment, why doesn't the phone company charge

you for the call the way it charges its own equipment?"

"Okay. That's where the 2600-cycle tone

comes in. I better start from the beginning."

The beginning he describes for me is a vision

of the phone system of the continent as thousands

of webs, of long-line trunks radiating from each

of the hundreds of toll switching offices to

the other toll switching offices. Each toll switching

office is a hive compacted of thousands of long-distance

tandems constantly whistling and beeping to tandems

in far-off toll switching offices. The tandem

is the key to the whole system. Each tandem is

a line with some relays wih the capability of

signalling any other tandem in any other toll

switching office on the continent, either directly

one-to-one or by programming a roundabout route

through several other tandems if all the direct

routes are busy. For instance, if you want to

call from New York to Los Angeles and traffic

is heavy on all direct trunks between the two

cities, your tandem in New York is programmed

to try the next best route, which may send you

down to a tandem in New Orleans, then up to San

Francisco, or down to a New Orleans tandem, back

to an Atlanta tandem, over to an Albuquerque

tandem and finally up to Los Angeles.

When a tandem is not being used, when it's sitting

there waiting for someone to make a long-distance

call, it whistles. One side of the tandem, the

side "facing" your home phone, whistles

at 2600 cycles per second toward all the home

phones serviced by the exchange, telling them

it is at their service, should they be interested

in making a long-distance call. The other side

of the tandem is whistling 2600 c.p.s. into one

or more long-distance trunk lines, telling the

rest of the phone system that it is neither sending

nor receiving a call through that trunk at the

moment, that it has no use for that trunk at

the moment.

"When you dial a long-distance number the

first thing that happens is that you are hooked

into a tandem. A register comes up to the side

of the tandem facing away from you and presents

that side with the number you dialed. This sending

side of the tandem stops whistling 2600 into

its trunk line. When a tandem stops the 2600

tone it has been sending through a trunk, the

trunk is said to be "seized," and is

now ready to carry the number you have dialed

-- converted into multi-frequency beep tones

-- to a tandem in the area code and central office

you want.

Now when a blue-box operator wants to make a

call from New Orleans to New York he starts by

dialing the 800 number of a company which might

happen to have its headquarters in Los Angeles.

The sending side of the New Orleans tandem stops

sending 2600 out over the trunk to the central

office in Los Angeles, thereby seizing the trunk.

Your New Orleans tandem begins sending beep tones

to a tandem it has discovered idly whistling

2600 cycles in Los Angeles. The receiving end

of that L.A. tandem is seized, stops whistling

2600, listens to the beep tones which tell it

which L.A. phone to ring, and starts ringing

the 800 number. Meanwhile a mark made in the

New Orleans office accounting tape notes that

a call from your New Orleans phone to the 800

number in L.A. has been initiated and gives the

call a code number. Everything is routine so

far. But then the phone phreak presses his blue

box to the mouthpiece and pushes the over the

line again and assumes that New Orleans has hung

up because the trunk is whistling as if idle.

The L.A. tandem immediately ceases ringing the

L.A. 800 number. But as soon as the phreak takes

his finger off the 2600 button, the L.A. tandem

assumes the trunk is once again being used because

the 2600 is gone, so it listens for a new series

of digit tones - to find out where it must send

the call.

Thus the blue-box operator in New Orleans now

is in touch with a tandem in L.A. which is waiting

like an obedient genie to be told what to do

next. The blue-box owner then beeps out the ten

digits of the New York number which tell the

L.A. tandem to relay a call to New York City.

Which it promptly does. As soon as your party

picks up the phone in New York, the side of the

New Orleans tandem facing you stops sending 2600

cycles to you and stars carrying his voice to

you by way of the L.A. tandem. A notation is

made on the accounting tape that the connection

has been made on the 800 call which had been

initiated and noted earlier. When you stop talking

to New York a notation is made that the 800 call

has ended.

At three the next morning, when the phone company's

accounting computer starts reading back over

the master accounting tape for the past day,

it records that a call of a certain length of

time was made from your New Orleans home to an

L.A. 800 number and, of course, the accounting

computer has been trained to ignore those toll-free

800 calls when compiling your monthly bill.

"All they can prove is that you made an

800 toll-free call," Gilbertson the inventor

concludes. "Of course, if you're foolish

enough to talk for two hours on an 800 call,

and they've installed one of their special anti-fraud

computer programs to watch out for such things,

they may spot you and ask why you took two hours

talking to Army Recruiting's 800 number when

you're 4-F. But if you do it from a pay phone,

they may discover something peculiar the next

day -- if they've got a blue-box hunting program

in their computer -- but you'll be a long time

gone from the pay phone by then. Using a pay

phone is almost guaranteed safe."

"What about the recent series of blue-box

arrests all across the country -- New York, Cleveland,

and so on?" I asked. "How were they

caught so easily?" "From what I can

tell, they made one big mistake: they were seizing

trunks using an area code plus 555-1212 instead

of an 800 number. Using 555 is easy to detect

because when you send multi-frequency beep tones

of 555 you get a charge for it on your tape and

the accounting computer knows there's something

wrong when it tries to bill you for a two-hour

call to Akron, Ohio, information, and it drops

a trouble card which goes right into the hands

of the security agent if they're looking for

blue-box user.

"Whoever sold those guys their blue boxes

didn't tell them how to use them properly, which

is fairly irresponsible. And they were fairly

stupid to use them at home all the time.

"But what those arrests really mean is

than an awful lot of blue boxes are flooding

into the country and that people are finding

them so easy to make that they know how to make

them before they know how to use them. Ma Bell

is in trouble."

And if a blue-box operator or a cassette-recorder

phone phreak sticks to pay phones and 800 numbers,

the phone company can't stop them? "Not

unless they change their entire nationwide long-lines

technology, which will take them a few billion

dollars and twenty years. Right now they can't

do a thing. They're screwed."

Captain Crunch Demonstrates His Famous

Unit

There is an underground telephone network in

this country. Gilbertson discovered it the very

day news of his activities hit the papers. That

evening his phone began ringing. Phone phreaks

from Seattle, from Florida, from New York, from

San Jose, and from Los Angeles began calling

him and telling him about the phone-phreak network.

He'd get a call from a phone phreak who'd say

nothing but, "Hang up and call this number."

When he dialed the number he'd find himself

tied into a conference of a dozen phone phreaks

arranged through a quirky switching station in

British Columbia. They identified themselves

as phone phreaks, they demonstrated their homemade

blue boxes which they called "M-Fers" (for

"multi-frequency," among other things)

for him, they talked shop about phone-phreak

devices. They let him in on their secrets on

the theory that if the phone company was after

him he must be trustworthy. And, Gilbertson recalls,

they stunned him with their technical sophistication.

I ask him how to get in touch with the phone-phreak

network. He digs around through a file of old

schematics and comes up with about a dozen numbers

in three widely separated area codes.

"Those are the centers," he tells

me. Alongside some of the numbers he writes in

first names or nicknames: names like Captain

Crunch, Dr. No, Frank Carson (also a code word

for a free call), Marty Freeman (code word for

M-F device), Peter Perpendicular Pimple, Alefnull,

and The Cheshire Cat. He makes checks alongside

the names of those among these top twelve who

are blind. There are five checks.

I ask him who this Captain Crunch person is.

"Oh. The Captain. He's probably the most

legendary phone phreak. He calls himself Captain

Crunch after the notorious Cap'n Crunch 2600

whistle."

(Several years ago, Gilbertson explains, the

makers of Cap'n Crunch breakfast cereal offered

a toy-whistle prize in every box as a treat for

the Cap'n Crunch set. Somehow a phone phreak

discovered that the toy whistle just happened

to produce a perfect 2600-cycle tone. When the

man who calls himself Captain Crunch was transferred

overseas to England with his Air Force unit,

he would receive scores of calls from his friends

and "mute"

them -- make them free of charge to them -- by

blowing his Cap'n Crunch whistle into his end.)

"Captain Crunch is one of the older phone

phreaks," Gilbertson tells me. "He's

an engineer who once got in a little trouble

for fooling around with the phone, but he can't

stop. Well, they guy drives across country in

a Volkswagen van with an entire switchboard and

a computerized super-sophisticated M-F-er in

the back. He'll pull up to a phone booth on a

lonely highway somewhere, snake a cable out of

his bus, hook it onto the phone and sit for hours,

days sometimes, sending calls zipping back and

forth across the country, all over the world...."

Back at my motel, I dialed the number he gave

me for "Captain Crunch" and asked for

G---- T-----, his real name, or at least the

name he uses when he's not dashing into a phone

booth beeping out M-F tones faster than a speeding

bullet and zipping phantomlike through the phone

company's long-distance lines. When G---- T-----

answered the phone and I told him I was preparing

a story for Esquire about phone phreaks, he became

very indignant.

"I don't do that. I don't do that anymore

at all. And if I do it, I do it for one reason

and one reason only. I'm learning about a system.

The phone company is a System. A computer is

a System, do you understand? If I do what I do,

it is only to explore a system. Computers, systems,

that's my bag. The phone company is nothing but

a computer."

A tone of tightly restrained excitement enters

the Captain's voice when he starts talking about

systems. He begins to pronounce each syllable

with the hushed deliberation of an obscene caller.

Captain

Crunch's own account of his phreaker days

"Ma Bell is a system I want to explore.

It's a beautiful system, you know, but Ma Bell

screwed up. It's terrible because Ma Bell is

such a beautiful system, but she screwed up.

I learned how she screwed up from a couple of

blind kids who wanted me to build a device. A

certain device. They said it could make free

calls. I wasn't interested in free calls. But

when these blind kids told me I could make calls

into a computer, my eyes lit up. I wanted to

learn about computers. I wanted to learn about

Ma Bell's computers. So I build the little device,

but I built it wrong and Ma Bell found out. Ma

Bell can detect things like that. Ma Bell knows.

So I'm strictly rid of it now. I don't do it.

Except for learning purposes."

He pauses. "So you want to write an article.

Are you paying for this call? Hang up and call

this number." He gives me a number in a

area code a thousand miles away of his own. I

dial the number. "Hello again. This is Captain

Crunch. You are speaking to me on a toll-free

loop-around in Portland, Oregon. Do you know

what a toll-free loop around is? I'll tell you.

He explains to me that almost every exchange

in the country has open test numbers which allow

other exchanges to test their connections with

it. Most of these numbers occur in consecutive

pairs, such as 302 956-0041 and 302 956-0042.

Well, certain phone phreaks discovered that if

two people from anywhere in the country dial

the two consecutive numbers they can talk together

just as if one had called the other's number,

with no charge to either of them, of course.

"Now our voice is looping around in a 4A

switching machine up there in Canada, zipping

back down to me," the Captain tells me. "My

voice is looping around up there and back down

to you. And it can't ever cost anyone money.

The phone phreaks and I have compiled a list

of many many of these numbers. You would be surprised

if you saw the list. I could show it to you.

But I won't. I'm out of that now. I'm not out

to screw Ma Bell. I know better. If I do anything

it's for the pure knowledge of the System. You

can learn to do fantastic things. Have you ever

heard eight tandems stacked up? Do you know the

sound of tandems stacking and unstacking? Give

me your phone number. Okay. Hang up now and wait

a minute."

Slightly less than a minute later the phone

rang and the Captain was on the line, his voice

sounding far more excited, almost aroused. "I

wanted to show you what it's like to stack up

tandems. To stack up tandems." (Whenever

the Captain says "stack up" it sounds

as if he is licking his lips.)

"How do you like the connection you're

on now?" the Captain asks me. "It's

a raw tandem. A raw tandem. Ain't nothin' up

to it but a tandem. Now I'm going to show you

what it's like to stack up. Blow off. Land in

a far away place. To stack that tandem up, whip

back and forth across the country a few times,

then shoot on up to Moscow.

"Listen," Captain Crunch continues.

"Listen. I've got line tie on my switchboard

here, and I'm gonna let you hear me stack and

unstack tandems. Listen to this. It's gonna blow

your mind."

First I hear a super rapid-fire pulsing of the

flutelike phone tones, then a pause, then another

popping burst of tones, then another, then another.

Each burst is followed by a beep-kachink sound.

"We have now stacked up four tandems,"

said Captain Crunch, sounding somewhat remote.

"That's four tandems stacked up. Do you

know what that means? That means I'm whipping

back and forth, back and forth twice, across

the country, before coming to you. I've been

known to stack up twenty tandems at a time. Now,

just like I said, I'm going to shoot up to Moscow."

There is a new, longer series of beeper pulses

over the line, a brief silence, then a ring.

"Hello," answers a far-off voice.

"Hello. Is this the American Embassy Moscow?"

Moscow?"

"Okay?"

"Well, yes, how are things there?"

"Oh. Well, everything okay, I guess."

"Okay. Thank you."

They hang up, leaving a confused series of beep-kachink

sounds hanging in mid-ether in the wake of the

call before dissolving away.

The Captain is pleased. "You believe me

now, don't you? Do you know what I'd like to

do? I'd just like to call up your editor at Esquire

and show him just what it sounds like to stack

and unstack tandems. I'll give him a show that

will blow his mind. What's his number?

I ask the Captain what kind of device he was

using to accomplish all his feats. The Captain

is pleased at the question.

"You could tell it was special, couldn't

you?" Ten pulses per second. That's faster

than the phone company's equipment. Believe me,

this unit is the most famous unit in the country.

There is no other unit like it. Believe me."

"Yes, I've heard about it. Some other phone

phreaks have told me about it." "They

have been referring to my, ahem, unit? What is

it they said? Just out of curiosity, did they

tell you it was a highly sophisticated computer-operated

unit, with acoustical coupling for receiving

outputs and a switch-board with multiple-line-tie

capability? Did they tell you that the frequency

tolerance is guaranteed to be not more than .05

percent? The amplitude tolerance less than .01

decibel? Those pulses you heard were perfect.

They just come faster than the phone company.

Those were high-precision op-amps. Op-amps are

instrumentation amplifiers designed for ultra-stable

amplification, super-low distortion and accurate

frequency response. Did they tell you it can

operate in temperatures from -55 degrees C to

+125 degrees C?"

I admit that they did not tell me all that.

"I built it myself," the Captain goes

on. "If you were to go out and buy the components

from an industrial wholesaler it would cost you

at least $1500. I once worked for a semiconductor

company and all this didn't cost me a cent. Do

you know what I mean? Did they tell you about

how I put a call completely around the world?

I'll tell you how I did it. I M-Fed Tokyo inward,

who connected me to India, India connected me

to Greece, Greece connected me to Pretoria, South

Africa, South Africa connected me to South America,

I went from South America to London, I had a

London operator connect me to a New York operator,

I had New York connect me to a California operator

who rang the phone next to me. Needless to say

I had to shout to hear myself. But the echo was

far out. Fantastic. Delayed. It was delayed twenty

seconds, but I could hear myself talk to myself."

"You mean you were speaking into the mouthpiece

of one phone sending your voice around the world

into your ear through a phone on the other side

of your head?" I asked the Captain. I had

a vision of something vaguely autoerotic going

on, in a complex electronic way.

"That's right," said the Captain. "I've

also sent my voice around the world one way,

going east on one phone, and going west on the

other, going through cable one way, satellite

the other, coming back together at the same time,

ringing the two phones simultaneously and picking

them up and whipping my voice both ways around

the world back to me. Wow. That was a mind blower."

"You mean you sit there with both phones

on your ear and talk to yourself around the world,"

I said incredulously.

"Yeah. Um hum. That's what I do. I connect

the phone together and sit there and talk."

"What do you say? What do you say to yourself

when you're connected?"

"Oh, you know. Hello test one two three,"

he says in a low-pitched voice.

"Hello test one two three," he replied

to himself in a high-pitched voice.

"Hello test one two three," he repeats

again, low-pitched.

"Hello test one two three," he replies,

high-pitched.

"I sometimes do this: Hello Hello Hello

Hello, Hello, hello," he trails off and

breaks into laughter.

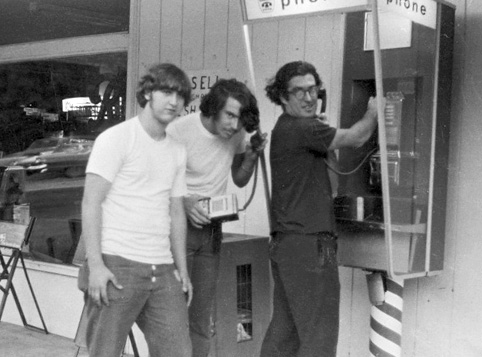

Early phreaks on “phone trip” to tinker with payphones.

Image: Mark Bernay or Bob Gudgel ?

Why Captain Crunch Hardly Ever Taps Phones

Anymore

Using internal phone-company codes, phone phreaks

have learned a simple method for tapping phones.

Phone-company operators have in front of them

a board that holds verification jacks. It allows

them to plug into conversations in case of emergency,

to listen in to a line to determine if the line

is busy or the circuits are busy. Phone phreaks

have learned to beep out the codes which lead

them to a verification operator, tell the verification

operator they are switchmen from some other area

code testing out verification trunks. Once the

operator hooks them into the verification trunk,

they disappear into the board for all practical

purposes, slip unnoticed into any one of the

10,000 to 100,000 numbers in that central office

without the verification operator knowing what

they're doing, and of course without the two

parties to the connection knowing there is a

phantom listener present on their line. Toward

the end of my hour-long first conversation with

him, I asked the Captain if he ever tapped phones.

"Oh no. I don't do that. I don't think

it's right," he told me firmly. "I

have the power to do it but I don't... Well one

time, just one time, I have to admit that I did.

There was this girl, Linda, and I wanted to find

out... you know. I tried to call her up for a

date. I had a date with her the last weekend

and I thought she liked me. I called her up,

man, and her line was busy, and I kept calling

and it was still busy. Well, I had just learned

about this system of jumping into lines and I

said to myself, 'Hmmm. Why not just see if it

works. It'll surprise her if all of a sudden

I should pop up on her line. It'll impress her,

if anything.' So I went ahead and did it. I M-Fed

into the line. My M-F-er is powerful enough when

patched directly into the mouthpiece to trigger

a verification trunk without using an operator

the way the other phone phreaks have to.

"I slipped into the line and there she

was talking to another boyfriend. Making sweet

talk to him. I didn't make a sound because I

was so disgusted. So I waited there for her to

hang up, listening to her making sweet talk to

the other guy. You know. So as soon as she hung

up I instantly M-F-ed her up and all I said was,

'Linda, we're through.' And I hung up. And it

blew her head off. She couldn't figure out what

the hell happened.

"But that was the only time. I did it thinking

I would surprise her, impress her. Those were

all my intentions were, and well, it really kind

of hurt me pretty badly, and... and ever since

then I don't go into verification trunks."

Moments later my first conversation with the

Captain comes to a close.

"Listen," he says, his spirits somewhat

cheered, "listen. What you are going to

hear when I hang up is the sound of tandems unstacking.

Layer after layer of tandems unstacking until

there's nothing left of the stack, until it melts

away into nothing. Cheep, cheep, cheep, cheep,"

he concludes, his voice descending to a whisper

with each cheep.

He hangs up. The phone suddenly goes into four

spasms: kachink cheep. Kachink cheep kachink

cheep kachink cheep, and the complex connection

has wiped itself out like the Cheshire cat's

smile.

The MF Boogie Blues

The next number I choose from the select list

of phone-phreak alumni, prepared for me by the

blue-box inventor, is a Memphis number. It is

the number of Joe Engressia, the first and still

perhaps the most accomplished blind phone phreak.

Three years ago Engressia was a nine-day wonder

in newspapers and magazines all over America

because he had been discovered whistling free

long-distance connections for fellow students

at the University of South Florida. Engressia

was born with perfect pitch: he could whistle

phone tones better than the phone-company's equipment.

Engressia might have gone on whistling in the

dark for a few friends for the rest of his life

if the phone company hadn't decided to expose

him. He was warned, disciplined by the college,

and the whole case became public. In the months

following media reports of his talent, Engressia

began receiving strange calls. There were calls

from a group of kids in Los Angeles who could

do some very strange things with the quirky General

Telephone and Electronics circuitry in L.A. suburbs.

There were calls from a group of mostly blind

kids in ----, California, who had been doing

some interesting experiments with Cap'n Crunch

whistles and test loops. There was a group in

Seattle, a group in Cambridge, Massachusetts,

a few from New York, a few scattered across the

country. Some of them had already equipped themselves

with cassette and electronic M-F devices. For

some of these groups, it was the first time they

knew of the others.

The exposure of Engressia was the catalyst that

linked the separate phone-phreak centers together.

They all called Engressia. They talked to him

about what he was doing and what they were doing.

And then he told them -- the scattered regional

centers and lonely independent phone phreakers

-- about each other, gave them each other's numbers

to call, and within a year the scattered phone-phreak

centers had grown into a nationwide underground.

Joe Engressia is only twenty-two years old now,

but along the phone-phreak network he is "the

old man," accorded by phone phreaks something

of the reverence the phone company bestows on

Alexander Graham Bell. He seldom needs to make

calls anymore. The phone phreaks all call him

and let him know what new tricks, new codes,

new techniques they have learned. Every night

he sits like a sightless spider in his little

apartment receiving messages from every tendril

of his web. It is almost a point of pride with

Joe that they call him.

But when I reached him in his Memphis apartment

that night, Joe Engressia was lonely, jumpy and

upset.

"God, I'm glad somebody called. I don't

know why tonight of all nights I don't get any

calls. This guy around here got drunk again tonight

and propositioned me again. I keep telling him

we'll never see eye to eye on this subject, if

you know what I mean. I try to make light of

it, you know, but he doesn't get it. I can head

him out there getting drunker and I don't know

what he'll do next. It's just that I'm really

all alone here, just moved to Memphis, it's the

first time I'm living on my own, and I'd hate

for it to all collapse now. But I won't go to

bed with him. I'm just not very interested in

sex and even if I can't see him I know he's ugly.

"Did you hear that? That's him banging

a bottle against the wall outside. He's nice.

Well forget about it. You're doing a story on

phone phreaks? Listen to this. It's the MF Boogie

Blues.

Sure enough, a jumpy version of Muskrat Ramble

boogies its way over the line, each note one

of those long-distance phone tones. The music

stops. A huge roaring voice blasts the phone

off my ear:

"AND THE QUESTION IS..." roars the

voice,

"CAN A BLIND PERSON HOOK UP AN AMPLIFIER

ON HIS OWN?" The roar ceases. A high-pitched

operator-type voice replaces it. "This is

Southern Braille Tel. & Tel. Have tone, will

phone."

This is succeeded by a quick series of M-F tones,

a swift "kachink" and a deep reassuring

voice: "If you need home care, call the

visiting-nurses association. First National time

in Honolulu is 4:32 p.m." Joe back in his

Joe voice again:

"Are we seeing eye to eye? 'Si, si,' said

the blind Mexican. Ahem. Yes. Would you like

to know the weather in Tokyo?" This swift

manic sequence of phone-phreak vaudeville stunts

and blind-boy jokes manages to keep Joe's mind

off his tormentor only as long as it lasts.

"The reason I'm in Memphis, the reason

I have to depend on that homosexual guy, is that

this is the first time I've been able to live

on my own and make phone trips on my own. I've

been banned from all central offices around home

in Florida, they knew me too well, and at the

University some of my fellow scholars were always

harassing me because I was on the dorm pay phone

all the time and making fun of me because of

my fat ass, which of course I do have, it's my

physical fatness program, but I don't like to

hear it every day, and if I can't phone trip

and I can't phone phreak, I can't imagine what

I'd do, I've been devoting three quarters of

my life to it.

"I moved to Memphis because I wanted to

be on my own as well as because it has a Number

5 crossbar switching system and some interesting

little independent phone-company districts nearby

and so far they don't seem to know who I am so

I can go on phone tripping, and for me phone

tripping is just as important as phone phreaking."

Phone tripping, Joe explains, begins with calling

up a central-office switch room. He tells the

switchman in a polite earnest voice that he's

a blind college student interested in telephones,

and could he perhaps have a guided tour of the

switching station? Each step of the tour Joe

likes to touch and feel relays, caress switching

circuits, switchboards, crossbar arrangements.

So when Joe Engressia phone phreaks he feels

his way through the circuitry of the country

garden of forking paths, he feels switches shift,

relays shunt, crossbars swivel, tandems engage

and disengage even as he hears -- with perfect

pitch -- his M-F pulses make the entire Bell

system dance to his tune. Just one month ago

Joe took all his savings out of his bank and

left home, over the emotional protests of his

mother. "I ran away from home almost," he

likes to say. Joe found a small apartment house

on Union Avenue and began making phone trips.

He'd take a bus a hundred miles south in Mississippi

to see some old-fashioned Bell equipment still

in use in several states, which had been puzzling.

He'd take a bus three hundred miles to Charlotte,

North Carolina, to look at some brand-new experimental

equipment. He hired a taxi to drive him twelve

miles to a suburb to tour the office of a small

phone company with some interesting idiosyncrasies

in its routing system. He was having the time

of his life, he said, the most freedom and pleasure

he had known.

In that month he had done very little long-distance

phone phreaking from his own phone. He had begun

to apply for a job with the phone company, he

told me, and he wanted to stay away from anything

illegal.

"Any kind of job will do, anything as menial

as the most lowly operator.

That's probably all they'd give me because I'm

blind. Even though I probably know more than

most switchmen. But that's okay. I want to work

for Ma Bell. I don't hate Ma Bell the way Gilbertson

and some phone phreaks do. I don't want to screw

Ma Bell. With me it's the pleasure of pure knowledge.

There's something beautiful about the system

when you know it intimately the way I do. But

I don't know how much they know about me here.

I have a very intuitive feel for the condition

of the line I'm on, and I think they're monitoring

me off and on lately, but I haven't been doing

much illegal. I have to make a few calls to switchmen

once in a while which aren't strictly legal,

and once I took an acid trip and was having these

auditory hallucinations as if I were trapped

and these planes were dive-bombing me, and all

of sudden I had to phone phreak out of there.

For some reason I had to call Kansas City, but

that's all."

A Warning Is Delivered

At this point -- one o'clock in my time zone

-- a loud knock on my motel-room door interrupts

our conversation. Outside the door I find a uniformed

security guard who informs me that there has

been an "emergency phone call" for

me while I have been on the line and that the

front desk has sent him up to let me know.

Two seconds after I say good-bye to Joe and

hang up, the phone rings. "Who were you

talking to?" the agitated voice demands.

The voice belongs to Captain Crunch. "I

called because I decided to warn you of something.

I decided to warn you to be careful. I don't

want this information you get to get to the radical

underground. I don't want it to get into the

wrong hands. What would you say if I told you

it's possible for three phone phreaks to saturate

the phone system of the nation. Saturate it.

Busy it out. All of it. I know how to do this.

I'm not gonna tell. A friend of mine has already

saturated the trunks between Seattle and New

York. He did it with a computerized M-F-er hitched

into a special Manitoba exchange. But there are

other, easier ways to do it."

Just three people? I ask. How is that possible?

"Have you ever heard of the long-lines

guard frequency? Do you know about stacking tandems

with 17 and 2600? Well, I'd advise you to find

out about it. I'm not gonna tell you. But whatever

you do, don't let this get into the hands of

the radical underground."

(Later Gilbertson, the inventor, confessed that

while he had always been skeptical about the

Captain's claim of the sabotage potential of

trunk-tying phone phreaks, he had recently heard

certain demonstrations which convinced him the

Captain was not speaking idly. "I think

it might take more than three people, depending

on how many machines like Captain Crunch's were

available. But even though the Captain sounds

a little weird, he generally turns out to know

what he's talking about.")

"You know," Captain Crunch continues

in his admonitory tone, "you know the younger

phone phreaks call Moscow all the time. Suppose

everybody were to call Moscow. I'm no right-winger.

But I value my life. I don't want the Commies

coming over and dropping a bomb on my head. That's

why I say you've got to be careful about who

gets this information."

The Captain suddenly shifts into a diatribe

against those phone phreaks who don't like the

phone company.

"They don't understand, but Ma Bell knows

everything they do. Ma Bell knows. Listen, is

this line hot? I just heard someone tap in. I'm

not paranoid, but I can detect things like that.

Well, even if it is, they know that I know that

they know that I have a bulk eraser. I'm very

clean." The Captain pauses, evidently torn

between wanting to prove to the phone-company

monitors that he does nothing illegal, and the

desire to impress Ma Bell with his prowess. "Ma

Bell knows how good I am. And I am quite good.

I can detect reversals, tandem switching, everything

that goes on on a line. I have relative pitch

now. Do you know what that means? My ears are

a $20,000 piece of equipment. With my ears I

can detect things they can't hear with their

equipment. I've had employment problems. I've

lost jobs. But I want to show Ma Bell how good

I am. I don't want to screw her, I want to work

for her. I want to do good for her. I want to

help her get rid of her flaws and become perfect.

That's my number-one goal in life now." The

Captain concludes his warnings and tells me he

has to be going.

"I've got a little action lined up for tonight,"

he explains and hangs up.

Before I hang up for the night, I call Joe Engressia

back. He reports that his tormentor has finally

gone to sleep -- "He's not blind drunk,

that's the way I get, ahem, yes; but you might

say he's in a drunken stupor." I make a

date to visit Joe in Memphis in two days.

A Phone Phreak Call Takes

Care of Business

The next morning I attend a gathering of four

phone phreaks in ----- (a California suburb).

The gathering takes place in a comfortable split-level

home in an upper-middle-class subdivision. Heaped

on the kitchen table are the portable cassette

recorders, M-F cassettes, phone patches, and

line ties of the four phone phreaks present.

On the kitchen counter next to the telephone

is a shoe-box-size blue box with thirteen large

toggle switches for the tones. The parents of

the host phone phreak, Ralph, who is blind, stay

in the living room with their sighted children.

They are not sure exactly what Ralph and his

friends do with the phone or if it's strictly

legal, but he is blind and they are pleased he

has a hobby which keeps him busy.

The group has been working at reestablishing

the historic "2111" conference, reopening

some toll-free loops, and trying to discover

the dimensions of what seem to be new initiatives

against phone phreaks by phone-company security

agents.

It is not long before I get a chance to see,

to hear, Randy at work. Randy is known among

the phone phreaks as perhaps the finest con man

in the game. Randy is blind. He is pale, soft

and pear-shaped, he wears baggy pants and a wrinkly

nylon white sport shirt, pushes his head forward

from hunched shoulders somewhat like a turtle

inching out of its shell. His eyes wander, crossing

and recrossing, and his forehead is somewhat

pimply. He is only sixteen years old.

But when Randy starts speaking into a telephone

mouthpiece his voice becomes so stunningly authoritative

it is necessary to look again to convince yourself

it comes from a chubby adolescent Randy. Imagine

the voice of a crack oil-rig foreman, a tough,

sharp, weather-beaten Marlboro man of forty.

Imagine the voice of a brilliant performance-fund

gunslinger explaining how he beats the Dow Jones

by thirty percent. Then imagine a voice that

could make those two He is speaking to a switchman

in Detroit. The phone company in Detroit had

closed up two toll-free loop pairs for no apparent

reason, although heavy use by phone phreaks all

over the country may have been detected. Randy

is telling the switchman how to open up the loop

and make it free again:

"How are you, buddy. Yeah. I'm on the board

in here in Tulsa, Oklahoma, and we've been trying

to run some tests on your loop-arounds and we

find'em busied out on both sides.... Yeah, we've

been getting a 'BY' on them, what d'ya say, can

you drop cards on 'em? Do you have 08 on your

number group? Oh that's okay, we've had this

trouble before, we may have to go after the circuit.

Here lemme give 'em to you: your frame is 05,

vertical group 03, horizontal 5, vertical file

3. Yeah, we'll hang on here.... Okay, found it?

Good. Right, yeah, we'd like to clear that busy

out. Right. All you have to do is look for your

key on the mounting plate, it's in your miscellaneous

trunk frame. Okay? Right. Now pull your key from

NOR over the LCT. Yeah. I don't know why that

happened, but we've been having trouble with

that one. Okay. Thanks a lot fella. Be seein'

ya."

Randy hangs up, reports that the switchman was

a little inexperienced with the loop-around circuits

on the miscellaneous trunk frame, but that the

loop has been returned to its free-call status.

Delighted, phone phreak Ed returns the pair

of numbers to the active-status column in his

directory. Ed is a superb and painstaking researcher.

With almost Talmudic thoroughness he will trace

tendrils of hints through soft-wired mazes of

intervening phone-company circuitry back through

complex linkages of switching relays to find

the location and identity of just one toll-free

loop. He spends hours and hours, every day, doing

this sort of thing. He has somehow compiled a

directory of eight hundred

"Band-six in-WATS numbers" located

in over forty states. Band-six in-WATS numbers

are the big 800 numbers -- the ones that can

be dialed into free from anywhere in the country.

Ed the researcher, a nineteen-year-old engineering

student, is also a superb technician. He put

together his own working blue box from scratch

at age seventeen. (He is sighted.) This evening

after distributing the latest issue of his in-WATS

directory (which has been typed into Braille

for the blind phone phreaks), he announces he

has made a major new breakthrough:

"I finally tested it and it works, perfectly.

I've got this switching matrix which converts

any touch-tone phone into an M-F-er."

The tones you hear in touch-tone phones are

not the M-F tones that operate the long-distance

switching system. Phone phreaks believe A.T.&T.

had deliberately equipped touch tones with a

different set of frequencies to avoid putting

the six master M-F tones in the hands of every

touch-tone owner. Ed's complex switching matrix

puts the six master tones, in effect put a blue

box, in the hands of every touch-tone owner.

Ed shows me pages of schematics, specifications

and parts lists. "It's not easy to build,

but everything here is in the Heathkit catalog."

Ed asks Ralph what progress he has made in his

attempts to reestablish a long-term open conference

line for phone phreaks. The last big conference

-- the historic "2111" conference --

had been arranged through an unused Telex test-board

trunk somewhere in the innards of a 4A switching

machine in Vancouver, Canada. For months phone

phreaks could M-F their way into Vancouver, beep

out 604 (the Vancouver area code) and then beep

out 2111 (the internal phone-company code for

Telex testing), and find themselves at any time,

day or night, on an open wire talking with an

array of phone phreaks from coast to coast, operators

from Bermuda, Tokyo and London who are phone-phreak

sympathizers, and miscellaneous guests and technical

experts. The conference was a massive exchange

of information. Phone phreaks picked each other's

brains clean, then developed new ways to pick

the phone company's brains clean. Ralph gave

M F Boogies concerts with his home-entertainment-type

electric organ, Captain Crunch demonstrated his

round-the-world prowess with his notorious computerized

unit and dropped leering hints of the "action"

he was getting with his girl friends. (The Captain

lives out or pretends to live out several kinds

of fantasies to the gossipy delight of the blind

phone phreaks who urge him on to further triumphs

on behalf of all of them.) The somewhat rowdy

Northwest phone-phreak crowd let their bitter

internal feud spill over into the peaceable conference

line, escalating shortly into guerrilla warfare;

Carl the East Coast international tone relations

expert demonstrated newly opened direct M-F routes

to central offices on the island of Bahrein in

the Persian Gulf, introduced a new phone-phreak

friend of his in Pretoria, and explained the

technical operation of the new Oakland-to Vietnam

linkages. (Many phone phreaks pick up spending

money by M-F-ing calls from relatives to Vietnam

G.I.'s, charging $5 for a whole hour of trans-Pacific

conversation.) Day and night the conference line

was never dead. Blind phone phreaks all over

the country, lonely and isolated in homes filled

with active sighted brothers and sisters, or

trapped with slow and unimaginative blind kids

in straitjacket schools for the blind, knew that

no matter how late it got they could dial up

the conference and find instant electronic communion

with two or three other blind kids awake over

on the other side of America. Talking together

on a phone hookup, the blind phone phreaks say,

is not much different from being there together.

Physically, there was nothing more than a two-inch-square

wafer of titanium inside a vast machine on Vancouver

Island. For the blind kids there meant an exhilarating

feeling of being in touch, through a kind of

skill and magic which was peculiarly their own.

Last April 1, however, the long Vancouver Conference

was shut off. The phone phreaks knew it was coming.

Vancouver was in the process of converting from

a step-by-step system to a 4A machine and the

2111 Telex circuit was to be wiped out in the

process. The phone phreaks learned the actual

day on which the conference would be erased about

a week ahead of time over the phone company's

internal-news-and-shop-talk recording.

For the next frantic seven days every phone

phreak in America was on and off the 2111 conference

twenty-four hours a day. Phone phreaks who were

just learning the game or didn't have M-F capability

were boosted up to the conference by more experienced

phreaks so they could get a glimpse of what it

was like before it disappeared. Top phone phreaks

searched distant area codes for new conference

possibilities without success. Finally in the

early morning of April 1, the end came.

"I could feel it coming a couple hours

before midnight," Ralph remembers. "You

could feel something going on in the lines. Some

static began showing up, then some whistling

wheezing sound. Then there were breaks. Some

people got cut off and called right back in,

but after a while some people were finding they

were cut off and couldn't get back in at all.

It was terrible. I lost it about one a.m., but

managed to slip in again and stay on until the

thing died... I think it was about four in the

morning. There were four of us still hanging

on when the conference disappeared into nowhere

for good. We all tried to M-F up to it again

of course, but we got silent termination. There

was nothing there."

The Legendary Mark Bernay Turns Out To

Be "The Midnight Skulker"

Mark Bernay. I had come across that name before.

It was on Gilbertson's select list of phone phreaks.

The California phone phreaks had spoken of a

mysterious Mark Bernay as perhaps the first and

oldest phone phreak on the West Coast. And in

fact almost every phone phreak in the West can

trace his origins either directly to Mark Bernay

or to a disciple of Mark Bernay. It seems that

five years ago this Mark Bernay (a pseudonym

he chose for himself) began traveling up and

down the West Coast pasting tiny stickers in

phone books all along his way. The stickers read

something like "Want to hear an interesting

tape recording? Call these numbers." The

numbers that followed were toll-free loop-around

pairs. When one of the curious called one of

the numbers he would hear a tape recording pre-hooked

into the loop by Bernay which explained the use

of loop-around pairs, gave the numbers of several

more, and ended by telling the caller, "At

six o'clock tonight this recording will stop

and you and your friends can try it out. Have

fun."

"I was disappointed by the response at

first,"

Bernay told me, when I finally reached him at

one of his many numbers and he had dispensed

with the usual "I never do anything illegal"

formalities which experienced phone phreaks open

most conversations.

"I went all over the coast with these stickers

not only on pay phones, but I'd throw them in

front of high schools in the middle of the night,

I'd leave them unobtrusively in candy stores,

scatter them on main streets of small towns.

At first hardly anyone bothered to try it out.

I would listen in for hours and hours after six

o'clock and no one came on. I couldn't figure

out why people wouldn't be interested. Finally

these two girls in Oregon tried it out and told

all their friends and suddenly it began to spread."

Before his Johny Appleseed trip Bernay had already

gathered a sizable group of early pre-blue-box

phone phreaks together on loop-arounds in Los

Angeles. Bernay does not claim credit for the

original discovery of the loop-around numbers.

He attributes the discovery to an eighteen-year-old

reform school kid in Long Beach whose name he

forgets and who, he says, "just disappeared

one day." When Bernay himself discovered

loop-arounds independently, from clues in his

readings in old issues of the Automatic Electric

Technical Journal, he found dozens of the reform-school

kid's friends already using them. However, it

was one of Bernay's disciples in Seattle that

introduced phone phreaking to blind kids. The

Seattle kid who learned about loops through Bernay's