In Memory of Jef Raskin, Macintosh Inventor

He Thought Different

March 9, 1943 - February 26, 2005

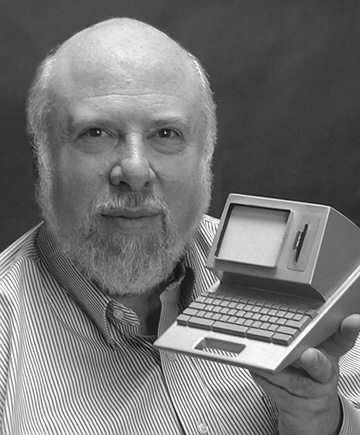

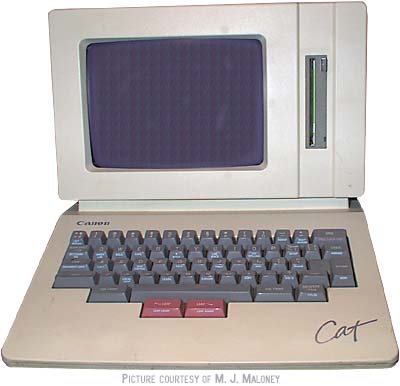

holds a model of one of his early computer designs,

the Canon CAT Computer from 1987. Courtesy of Aza Raskin. holds a model of one of his early computer designs,

the Canon CAT Computer from 1987. Courtesy of Aza Raskin.

We lost one of the great ones today,

a good and generous man.

Dave Burstein - February 26, 2005

Jef Raskin wasn't the typical tech industry power broker. He was never a celebrity CEO, never a Midas-touch venture capitalist, and never conspicuously wealthy (although he was wealthy). Yet until his Feb. 26 death at 61, the creator of the Macintosh led the rallying cry for easy-to-use computers, leaving an indelible mark on Silicon Valley and helping to revolutionize the computer industry.

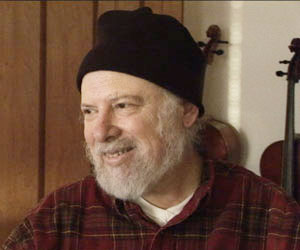

Jef Raskin, a mathematician, orchestral soloist and composer, professor, bicycle racer, model airplane designer, and pioneer in the field of human-computer interaction, died peacefully at home in California on February 26th, 2005 surrounded by his family and loved ones.

Jef Raskin was known as the "Father of the Macintosh'' for his early work designing what became Apple Computer Inc.'s signature product and the start of the personal computer revolution. Raskin joined Apple Computer in 1978 as employee number 31 and headed the company's Macintosh development team from its founding in 1982. He started at Apple in January 1978 as head of its publications department. Raskin assembled a design team and named the project after his favorite variety of apple, although with a slight change in the spelling of the McIntosh. From 1979 to 1982 Raskin was responsible at Apple for a research project called Macintosh.

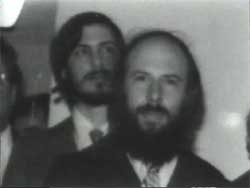

Steve Jobs and Jef Raskin in 1977, and the complete picture with Jobs in the back,

Raskin in the front and other Apple II team members.

He is credited with significantly advancing the design of user interfaces, which in the early 1980s were largely text-based and required users to memorize complex commands. Raskin convinced his peers at Apple that to reach a wider audience, the Macintosh needed an interface that was elegant and easy to use.

| Quote Jef Raskin: |

| "Up to that time, at Apple and most other manufacturers, the concept was to provide the latest and most powerful hardware, and let the users and third-party software vendors figure out how to make it usable," he wrote later on his Web site. |

In Raskin's paper The Genesis and History of the Macintosh Project (February 1981) he provided his thoughts on the main software design criteria for the Macintosh:

| Quote Jef Raskin: |

| My concepts in designing the software were extreme ease of learning, rapid (and thus non frustrating) response to user desires, and compact and quickly developable software. Key elements in designing such a system are freedom from modes, the elimination of "levels" (e.g. system level, editor level, programming level), and repeated use of a few consistent and easily learned concepts. Such software also leads to simple and brief manuals without having to sacrifice completeness and accuracy. The editor is similar to the LISA editor but does not require the expensive mouse. A careful study showed that is is probably faster to use than a mouse driven editor -- although it is probably not as flashy to see when demonstrated in a dealer's showroom. |

On a recent visit (January 29, 2005) visit with Jef and his family, Jef gave digibarn Museum a tour of some of his amazing artifacts (including his Apple I. Photos and an interview in MP3 Audio, recorded at Raskin´s home on Jan 29, 2005 at http://www.digibarn.com/friends/jef-raskin/

Apple historians note that Raskin, who joined the Cupertino firm in 1978 as its 31st employee, began working on a proposal in March 1979 for Apple to construct an inexpensive computer tailored to the way humans would operate it instead of how the device processed applications.

Raskin even proposed the company start an "Apple Computer Network'' to connect the computers and give them more appeal to average consumers who could use them to send birthday greetings, check stock quotes, look up television guides, check travel information and for computer dating.

"Jef was the first person at Apple to be passionate about usability, and we all learned a lot from him,'' said Andy Hertzfeld, a key architect of the original Macintosh operating system software. "He always reminded us that people were far more important than computers, and to always keep the user in the center of our thinking.''

But the Macintosh that Apple introduced in 1984 was "vastly different'' than the one Raskin envisioned, said Owen Linzmayer, author of the book "Apple Confidential.'' That's because Apple co-founder and current Chief Executive Officer Steve Jobs, bumped from the company's high-end Lisa computer project, took over the Macintosh project in 1981 and "pushed it in the direction he wanted it to go.''

The two clashed over the design areas such as Jobs' insistence on using a computer mouse, while Raskin advocated a joystick type of device, Linzmayer said. Apple CEO Steve Jobs took over the Macintosh project, and Raskin left the company. It was a hard time for him and many of those who worked closely with him, Tognazzini says. "Mac was his brainchild," Tognazzini says. "The interface in the early days wasn't what ended up shipping, but the philosophy behind it was his."

In 1994 Raskin had the following to say about the original Macintosh's software design (The Mac and Me: 15 Years of Life with the Macintosh):

| Quote Jef Raskin: |

| My unifying software originally was to be a graphics-and-text editor within which applications could run as additional commands (via menus), all input and output being through the interface designed for the editor. Later, the PARC desktop metaphor was adopted from the Lisa group (and that from the Xerox Alto and the Star computers). Due to the incredible work of the Mac software team, the necessary code was designed and squeezed into a Toolbox that fit into a relatively small ROM (Read Only Memory) that we could afford to put into the product. |

Raskin also had some interesting comments to say in one of his many Macintosh design memos concerning the intended users of the Macintosh (Design Considerations for an Anthropophilic Computer, 28-29 May 1979):

| Quote Jef Raskin: |

| This is an outline for a computer designed for the Person In The Street (or, to abbreviate: the PITS); one that will be truly pleasant to use, that will require the user to do nothing that will threaten his or her perverse delight in being able to say: "I don't know the first thing about computers". |

"He (Jef Raskin) started the Macintosh project," Aza Raskin said of his father. "It was canceled (but restarted by Raskin) three different times." With a rivalry with Jobs creating tension on the project, "Jeff decided that rather than play political games, he would move on and 'do it right,' as he said," Aza Raskin recalled. "Steve Jobs and Jeff came close to reconciling toward the end," Aza Raskin added. "When the millionth Mac was made, Jobs gave it to him with his name engraved.""

Raskin left Apple in 1982, two years before the Macintosh went on sale, but he continued to influence the design of computers through his writing, lectures, and consulting work. Soon after leaving the company he founded Information Appliance, where he designed the Canon Cat computer for Canon USA.

Information Appliances goal was to create a computer system that would be both powerful and easy to use. The company developed a prototype Cat system code named "SWYFT". Doug McKenna, a former company director and now the key person behind the Macintosh development tool Resorcerer, said that he proposed that "SWYFT" be read as "Superb With Your Favorite Typing" (personal phone call, 15 June 1994). Funding for this company came from around a dozen venture capitalists. Jef Raskin told Newswireless.net's Guy Kewney in his house in the hills above Palo Alto:

| Quote Jef Raskin: |

| Obituary a computer is a device for running programs. An Information Appliance is something with a processor in it, but which has a function. This software is The Information Appliance.' |

And he demonstrated his software, running on an old Apple II, and it was amazing. Everything he did was amazing. Guy Kewney ran into him at a San Francisco party given shortly after the launch of the Apple Mac which, Raskin told him, interrupting a conversation with Jim Warren to say: "You really ought to interview me, you know!"...

The CAT Computer wasn't a commercial success, which Raskin's family and friends blame on Canon's marketing, which pitched the product to secretaries, a niche for which he hadn't intended it. The Canon Cat sold fewer than 20,000 units and was then abandoned. "Jef was a true genius at many things, but not at promotion," says Burstein. Despite the rapid sale of twenty thousand units, Canon terminated the project due to an internal dispute. Some Canon Cat owners report continuing to use their Cats to this day.

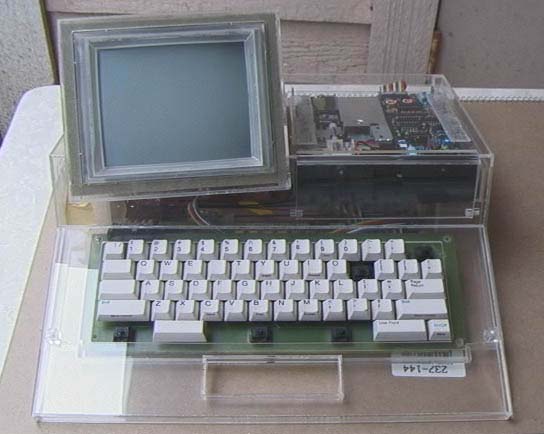

This is the prototype Cat system code named "SWYFT" Raskin

designed for Canon after leaving Apple. Courtessy of www.jagshouse.com

The Macintosh's early hardware design was very similar to the Cat's design. One early Macintosh design from January 1980 provided a small screen, a keyboard, and two vertical built-in disk drives. Also present in this early Macintosh design was a built-in printer.

Raskin had the following to say about the Cat and the Apple Macintosh in a personal letter dated July 1987:

| Quote Jef Raskin: |

| It is as advanced (in terms of human interface) over the Mac as the Mac was an advance in its day. |

Raskin's thoughts on the Cat's user interface and other user interfaces from the perspective of 1994 follow (The Mac and Me: 15 Years of Life with the Macintosh, Draft copy, May 1994):

| Quote Jef Raskin: |

The current paradigm of using application programs is inherently wrong from an interface design point of view. This is widely recognized, but the solution offered is to make them inter operable, which solves some of the problems but by no means all. GUIs as presently designed and used are an interface dead end. Though they can be patched endlessly, a large jump in usability can only come from a completely different approach. The Cat computer, which I developed for Canon, demonstrated that my alternate approach is implementable and both more productive and more pleasant than GUIs.

|

Courtessy of www.old-computers.com

Read about the Canon's Cat Computer: The Real Macintosh

Raskin viewed good design as a moral duty, holding interface designers to the same ethical standards as surgeons. He was currently at work on a project called Archy, where he hoped to put many of the ideas expressed in his book into software. Archy uses simple commands for common operations in word processing and e-mail, but "doesn't work like anything else on this or nearby planets," meaning users would have to learn it from scratch, he wrote on his Web site.

Alluding to Isaac Asimov's first law of robotics, one of Raskin's mantras was that 'any system shall not harm your content or, through inaction, allow your content to come to harm'. Archy implements that principle by making it impossible to permanently lose your work. Archy also replaces mouse movements, which many text editing programs require, with much faster "Leap" keystrokes, reducing the likelihood of carpel tunnel syndrome.

| Quote Jef Raskin: |

| One of his biggest legacies after the Mac is turning interface design into an engineering discipline,'' said his son, Aza Raskin, 21, who was working with his father to develop the new Archy computer program. The program - named after a fictional cockroach in an early 20th century newspaper column - is designed to work with any operating system. It eliminates the desktop seen on computer screens and other "useless'' features such as dialogue boxes, Aza Raskin said. |

Jef Raskin had hoped to release the prototype of Archy today. But Aza Raskin said he and the design team are still planning to release the project sometime this month.

"It was a race nearly to the end,'' Raskin's son Aza Raskin said Monday. "Jef was working on Archy until he really couldn't type anymore. That was around a week ago.'' Jef Raskin insisted on continuing his work to the end. "He said, 'I don't want pity or anything else, I just want to work and get my ideas out,' '' Aza Raskin said. But even in his final days, Raskin held fast to his belief that computers are still not as easy to operate as they could be and worked to design more "humane'' ways for people to use PCs.

Raskin worked until the last days of his life to finish the code for Archy. He told a friend ten days before he died: 'When people get a chance to work in Archy and see how much easier it is to do their work, we'll get enormous support.' He had completed almost all of the basic work by the time his health took a turn for the worse a few days later.

Recent Projects

Jef Raskin consulting clients have included Intel, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, and many other big names in computing. In 2000 he published a book, "The Humane Interface," that is widely assigned at universities.

In his 2000 book, "The Humane Interface", Raskin coined the term and founded the field of cognetics, the ergonomics of the mind, transforming interface design into an engineering discipline with a rigorous theoretical framework. His book, translated into more than nine languages, has gone through numerous printings and become the standard text for more than 100 computing courses around the world. His son, Aza Raskin, will continue to develop the project´Archy, a preview version of which is due out later this year, his family says in the statement. Raskin lived most recently in Pacifica, California.

Macintosh Creator and "Humane Interface" author Jef Raskin

Raskin's interests were not restricted to computers: He taught the recorder, harpsichord, and music theory at San Francisco Community College in the 1970s, and his family described him as an orchestral soloist and composer. He also founded a company that designed and sold radio-controlled model aircraft.

|

![]()